By Shyamal Sinha

Buddhism in South east Asia includes a variety of traditions of Buddhism including two main traditions: Mahāyāna Buddhism and Theravāda Buddhis m. Historically, Mahāyāna Buddhism had a prominent position in this region, but in modern times most countries follow the Theravāda tradition.

South east Asian countries with a Theravāda Buddhist majority are Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia, Lao s, and Myanmar.

Vietnam continues to have a Mahāyāna majority due to Chinese influence. Indonesi a was Mahāyāna Buddhist since the time of the Sailendra and Srivijaya em pires, but now Mahāyāna Buddhism in Indonesia is now largely practiced by the Chinese diaspora, as in Singapore and Malaysia. Mahāyāna Buddhism is the predominant religion of most Chinese communities in Singapore. In Malaysia, Brunei, Philippin es and Indonesia, it remains a strong minority.

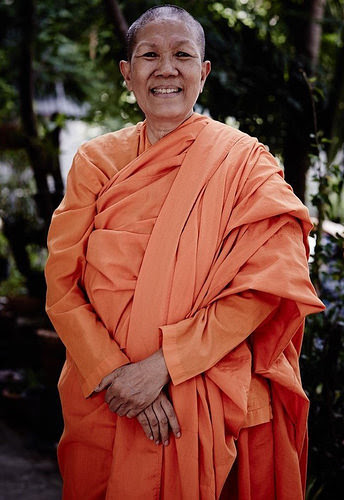

Despite entrenched opposition from within the conservative ranks of Buddhist officialdom that governs Thailand’s monastic community, the tiny but growing community of fully ordained female monastics in this Southeast Asian kingdom is steadily gaining recognition and respect and is increasingly viewed as occupying the forefront of a positive tide of change in a religious institution riven by reports of excess, corruption, and hypocrisy.

“Change is taking place in favor of female ordination, not only in Thailand but elsewhere in the world,” said Venerable Dhammananda Bhikkhuni, Thailand’s first fully ordained female monastic and something of a quiet figurehead for the movement. “Whatever the resistance from the establishment, more women will choose to pursue a spiritual path as female monastics. Nothing can stop it.” (Nikkei Asian Review)

Predominantly a Buddhist country—93.2 per cent of Thailand’s population of 69 million identify as Theravada Buddhists, according to data for 2010 from the Washington, DC-based Pew Research Center—Thailand is home to approximately 38,000 Buddhist temples and an estimated 300,000 bhikkhus. However, Thailand has never officially recognized the full monastic ordination of women, and bhikkhunis do not generally enjoy the same level of societal acceptance as their male counterparts. By comparison, the Mahayana branch of Buddhist traditions widely practiced in East Asia have historically been much more accepting of female ordination.

Yet communities of female renunciants do exist and are growing across Thailand. There are currently more than 100 determined bhikkhunis who are committed to overturning the institutionalized chauvinism that stands in the way of female monasticism. Supported by more progressively minded bhikkhus, they seek to re-establish the fourfold sangha* envisioned by Shakyamuni Buddha as the optimal holistic and inclusive structure in which all segments of society can study and share the Dharma.

fully ordained in the Theravada tradition. From

huffingtonpost.com

Ven. Dhammananda ordained in Sri Lanka in 2013, becoming Thailand’s first bhikkhuni in the face of considerable public opposition. Formerly known as Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, an author and professor of religious studies and philosophy at a prominent Thai university, she states her case simply and with a gentle logic, noting that the Buddha himself founded the bhikkhuni order, which included his own adoptive mother.

“When the Buddha was enlightened and he established the Buddhist religion, he described the four pillars of the faith: bhikkhu, bhikkhuni, laymen, and laywomen,” she explains. “This was very clear in his mind and it is written in the historical texts, so it is not about equality as such, it is about what’s right. We are shareholders of the faith and simply upholding Buddha’s original vision.” (Huffington Post)

According to historians, bhikkhunis flourished for 1,000 years in India and Sri Lanka, but the spread of Islam and the impact of various regional conflicts caused them to almost disappear. In Thailand, a proclamation by the kingdom’s Buddhist Sangha Supreme Council in 1928 expressly forbade female ordination. Instead, women in the country may only become white-robed nuns, known in Thai asmaechi, who receive a much lower level of respect and recognition from society at large, and hold a rank comparable to that of a novice monk.

Yet amid a stream of media reports of scandalous exploits by misbehaving monks, there is a growing public voice warning that patience is beginning to wear thin and calling for reform. “There are many questions posed by the public that the Sangha has to answer,” notes Phramaha Boonchuay Doojai, a leading activist monk at Chiang Mai Buddhist College: “They cannot just sit quietly and hope issues like female ordination will fade away. It is not possible.” (Nikkei Asian Review)

He warns that if the sangha’s bureaucracy continues to oppose bhikkhuni ordination, it could find itself at the wrong end of popular opinion after already drawing criticism for failing to curtail inappropriate behavior among the male monastic majority.

International attention and support has also lent impetus to the movement in recent years, with organizations such as the Network of Asian Theravada Bhikkhunis and the Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women adding weight to the growing consensus. In Thailand, Songdhammakalyani Monastery in the central town of Nakhon Pathom, of which Ven. Dhammananda is the abbot, has become an international center for the training of female Buddhist clergy.

“Change is taking place in favor of female ordination, not only in Thailand but elsewhere in the world,” said Ven. Dhammananda with optimism. “Whatever the resistance from the establishment, more women will choose to pursue a spiritual path as female monastics. Nothing can stop it.” (Nikkei Asian Review)

* The fourfold sangha: bhikkhus (male monastics), bhikkhunis (female monastics), upasakas (male lay followers), and upasikas (female lay followers.)