Their lives: Living in the harsh landscape, the people of Ladakh have to bow to the whims of nature and rely heavily on each other on a daily basis. (Source: Prerna Raturi)

Their lives: Living in the harsh landscape, the people of Ladakh have to bow to the whims of nature and rely heavily on each other on a daily basis. (Source: Prerna Raturi)We grumbled, disappointed that the teashop was shut. Having walked non-stop for three hours, even reaching out for our bottles for rationed sips of water seemed like an effort. We did rest, though, on makeshift stone benches, while some of us made half-hearted attempts to photograph the cloudless dazzling blue skies and the stark brown hills around us. Only Gurmet Angmo noticed the wilted sunflowers. She got up quietly, filled a plastic bottle from the shallow stream, and watered the plants. The shop wasn’t hers, and neither were the flowers.

A day later in Markha village, as we returned from the harvest scene, having taken selfies and videos, done the touristy thing of “helping” villagers, played with rosy-cheeked children, it was Angmo again who saw a calf mooing in desperation, craning its neck to reach its mother’s udder. She went near and coaxed the cow to get closer to the calf, who grasped the mother’s teat eagerly. The cow wasn’t hers and, in fact, neither was the village.

You can’t teach such empathy and kindness. But how easily it came to Angmo, a Ladakhi woman and the quietest person in our team of six, that had set out to electrify the 600-year-old monastery in Markha, the biggest village in the Markha Valley. Thirty-six-year-old Angmo was one of the two engineers who helped us put up a 250W solar panel, 20 3W bulbs, and one 18W streetlight, complete with holders, wiring and switches.

The other engineer, Stanzin Jigmet, was a shy Ladakhi who became my go-to person when it came to queries about Buddhism in Ladakh, wiring and electrical fittings, how to say “thank you” in Ladakhi, why people kept saying chikchik while offering us momos, and whether he could source some chhang, the local alcoholic beverage made of barley. He told me how Bon religion preceded Buddhism in Ladakh; that the wiring we got done was DC (direct current) and not the usual AC (alternate current); there are two ways to say thank you — jullay (which also means hi, please, okay, goodbye) and thugdzetche, which is more formal and respectful; that people were actually saying tchik tchik while offering us food — tchik meaning the numeric one — insisting we have one more; and there would be chhang for us.

At an altitude of 3,770 m, Markha village is on a popular trek circuit in Ladakh. And yet, the village and its monastery have little access to electricity. Although there are solar panels in some households, the technology allows for only four hours of power every day, from 6-10 pm. The light bulbs aren’t of any use on rainy and overcast afternoons either. Our expedition was organised by Global Himalayan Expedition (GHE), a social enterprise that takes responsible travellers to unelectrified villages, where they help provide solar energy to remote communities and create a life-long impact.

At least six women were supposed to be a part of GHE’s Women Leaders Expedition, but only two of us made it. There was a bright 24-year-old management graduate from Singapore, who is interning with an international energy company. And there was me, a middle-aged, pre-menopausal, podgy, white-haired woman hell bent on denying she gets her adrenaline dose from doing laundry, preparing frantic meals, juggling writing-editing deadlines, and handling a tea-addicted husband, the maid’s passive-aggressive personality, and a tween daughter’s mood swings.

Apart from giving me the happy-hormone rush, I crave for treks and expeditions because they let me be myself. Walking among the colours of autumn, passing through the tiny hamlets and vast open spaces, I don’t have to worry about my hairstyle or if my muddy worn-for-three days Navy blue pants matched the purple fleece jacket. No one asked me my marital status or my age, and none volunteered to help until I asked for it. Nature isn’t sexist or ageist either, and the freak snowfall one afternoon chilled all of us to the bone.

Boasting of some of the most stunning scenery, the newly-formed Union territory of Ladakh is also one of the world’s harshest landscapes. It has an average temperature of 5 degrees Celsius. July is the hottest at 17 degrees Celsius, and in January, the temperature can fall to -8 degrees Celsius; the cold and dry land has an annual precipitation of just 80 mm. Surviving in such harsh conditions means the people of Ladakh have to bow to the whims of nature and rely heavily on each other on a daily basis. Harvest time — barley and wheat, apart from local seasonal vegetables and potatoes — means entire populations of nearby villages pitch in to help each other; remember the empty tea shop I mentioned earlier? We were fortunate enough to witness a harvest, a communal festival of sorts — people sang and whistled, urged the winds to blow favourably so that winnowing the grain could become less tiresome, and took periodic breaks to sit in the sun and drink chhang.

In the village, people moved freely in and out of each other’s homes, knowing exactly where the reserved-for-guests cups were kept, and serving us chhang, khunak (black tea with salt), gur-gur cha (butter tea), milik tea (regular milk tea) or momos. It was impossible for me to figure out whose house it really was.

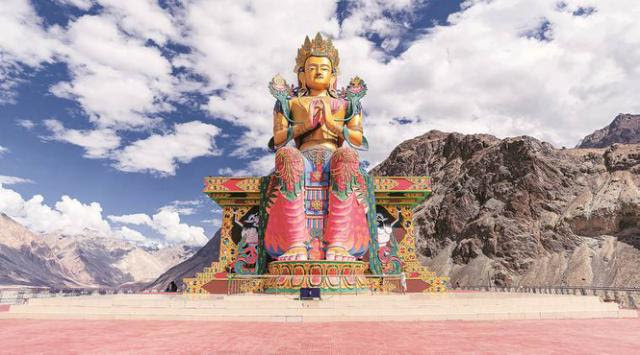

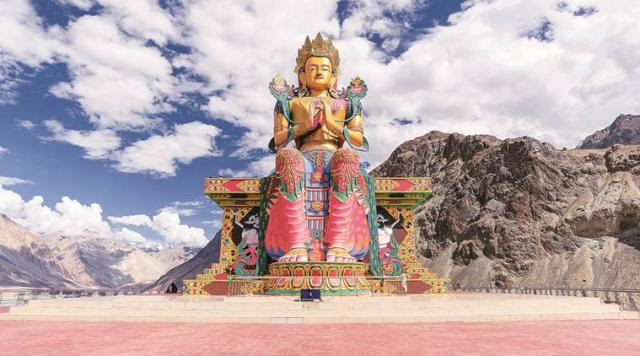

Just like the homes that are open to all — literally, since few people use locks — the monastery, too, is a place for people to come together to celebrate, discuss village matters, or to simply express gratitude. As Manjiri Gaikwad, GHE’s representative who accompanied us on the expedition, told me, “Without exception, the villagers always request that the monastery be electrified before their own homes.” For a people whose lives rely on so much they have no control over, most Ladakhis in rural areas put unshakeable trust in their religion and its seat — monasteries. Whether this faith will remain unshakeable with climate change hitting the fragile ecosystem in the form of flashfloods and cloudbursts, receding glaciers and drying rivers and streams and a rise in average temperature, is a question I hope they never have to answer.

The optimist in me did see positive change afoot as well. For instance, no shops I visited in Leh market gave out single-use plastic bags, and in my five days in Markha Valley, I didn’t see any bottled water for sale, with all homestays offering filtered water and a refill of the same at tea shops for Rs 20.

The most treasured moment of our trip remains the blurred-by-tears half-hour when the lights came on in the monastery at 7.30 pm. With whoops of joy and silent prayers, we offered the khatak (silk scarf offered as a mark of respect) to the MCB box (miniature circuit-breaker box). Villagers prostrated themselves in front of the idols and looked at the old fresco paintings on the walls with mouths agape. And, then, we all sat together that chilly evening and had black tea and biscuits together. “Usually, there is much dancing and singing after such ceremonies,” said Sonum Norbu, constituency area councillor, “but not this time. A villager’s sister died two months ago and we are in mourning.”

Thugdzetche, for all the lessons in kindness, Ladakh.

The writer is a coordinator for Earth Day Network in India. The expedition was a carbon-negative one.