By Shyamal Sinha

Buddhism

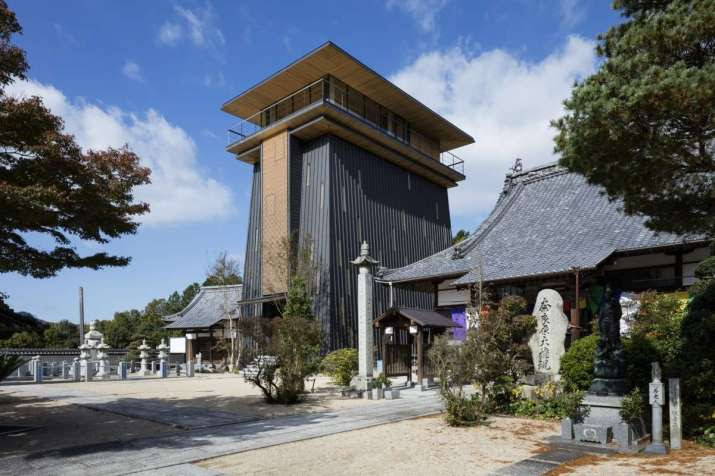

The new ihaidō—an ancestral hall or hall in a Japanese Buddhist temple where memorial tablets are enshrined—of the 1316-year-old Korin-Ji temple in Japan combines past, present, and future in its modernist design drawing on Japanese traditional aesthetics, a modern minimalist design, and a combination of both modern and traditional building materials.

Located in the northwest of Shikoku, in the mountains of Tamagawa-chō, Imabari city, Japan, Korin-Ji Temple is one of the hundreds of temples on Shikoku Island. The newihaidō building of the temple is part of a modernization of the complex to build a “temple for the future.”

To meet this brief, Architects Takashi Okuno & Associates created a five-story structure that oozes of both Japanese minimalism and traditional aesthetics and that does not seem out of place in the 1316-year old temple, or the mountains that are its home.

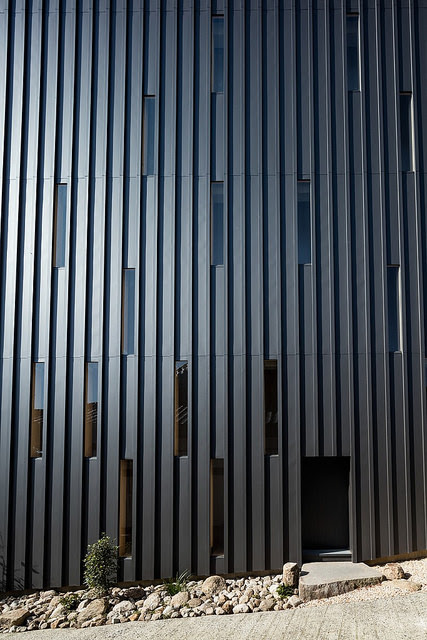

The building is made up out of two parts. The base, made of a steel framework which is covered by around 800 cypress rafters that are left exposed and are evoke of the pleads of a hakama—a traditional Japanese skirt-like garment worn over a kimono that is still part of the Aikido uniform. In between the rafters, 88 glass panes have been fitted in a seemingly random pattern that allow for natural light to filter into the all-wooden interior.

The number 88 holds special significance in Japanese Buddhism, as it represents the 88 Buddhas of Zen cosmology and is often used to denote “a great many” or “countless” in Japanese. In addition, the famous Shikoku pilgrimage or 四国遍路 Shikoku Henro consists out of 88 temples scattered across the island. Korin-Ji is not part of the pilgrimage but is known as one of the hundreds of (unrecognized) bangai (ban

(in white). From okunotakashi.jp

The colors and intensity of the light that enters the building through the 88 glass panes in thehakama skirt of the building shifts according to the seasons and the foliage surrounding the temple, bringing to mind the Buddhist principle of impermanence or shogyō mujō in Japanese (a poplar element in Japanese aesthetics). The light transforms the hakama frame into a corridor of light leading up to the highest floor where glass windows replace the wooden skirting allowing visitors to connect with the surrounding nature.

In addition to their aesthetic value, the wooden rafters also have a practical use as they protect the steel frame of the building from the powerful winds and rain that at times plague the temple grounds.

Due to the widely-distributed and readily available materials used for the hakama skirting and the roof, and the simple construction methods that have been deployed, local craftsmen will be able to easily complete any maintenance work the temple might require in the future.

The architects hope that the design of the ihaidō will bring comfort to those visiting Korin-Ji to commemorate their loved ones:

People think of their loved ones as they face the building and bring their hands together in prayer. It is our hope that the sprinkles of light climbing toward the heavens will serve as a source of comfort for people’s spirits.

(Takashi Okuno & Associates)