Palden Sonam

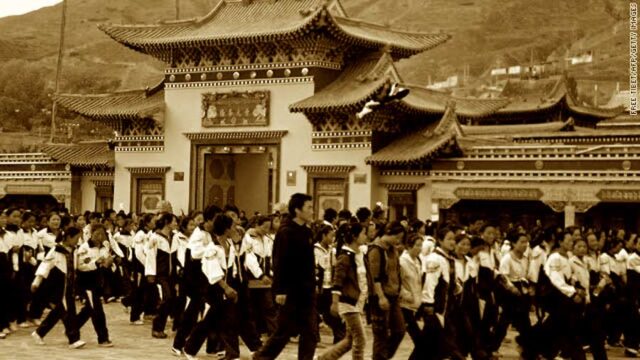

On July 12, a video clip from Tibet was going viral on the Tibetan cyber world, which, at first glance, appeared like a funeral ceremony. Everyone in the video looked visibly distraught with their heads down and many crying.

However, it turned out to be a scene from the final day of Ragya Sherig Norbu Lobling –a prominent private-run Tibetan school in Amdo region of Tibet as teachers and students paid their last respect to their beloved school after the Chinese government forced it to close.

In a normal situation, a school would be shut down if it failed to serve the primary goal of giving education to its students. In today’s occupied Tibet, however, a school can be forced to close simply because it is able to give great education to its students.

Ragya School was established in 1994 by Jigme Gyaltsen, a Tibetan monk educator in Golok, (Ch: Guoluo Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai). Golok is largely a remote nomadic area and this school has played a pivotal role in providing quality education to hundreds of Tibetan students. As its popularity spreads, students from different parts of Tibet have sought admission into it. Many of its students are orphans.

This school, in addition to providing both traditional and modern education –including Tibetan traditional medicine and handcrafts, computer and international languages like Chinese and English –has adopted the centuries-old techniques of Nalanda’s analytical debate to teach contemporary subjects. This teaching method proved to be a great success in the learning experience of the students. Some Chinese scholars have been so much impressed by the academic brilliance of the school’s students that they visited the school to observe it.

In fact, Ragya school and its founder won many official recognitions from Chinese government including Excellent Service Award (2003), China Charity Worker award (2005), National People’s Education award (2010) and Innovative School Award (2012) for its contribution to education and society.

Nevertheless, the aggressive assimilationist campaign, Chinese president Xi Jinping launched as the key feature of his repressive policy toward Tibetans and other colonized people like the Uyghurs, has drastically reduced their already limited space to teach and study and practice their language, culture and religion.

This policy is implemented on an aggressive scale –shutting down village-level schools, banning private Tibetan classes, displacing Tibetan as medium of instruction and putting thousands of children in colonial boarding schools. In May this year, China closed another Tibetan-run school, Taktsang Lhamo Tibetan Culture School in Amdo Ngaba (Sichuan). This school founded in 1986 played a key role in providing education to the local Tibetan children.

For Tibetans, this entho-nationalist war, on their language and culture, is not only an issue of language and cultural rights and repression, but also human rights violation and a crime against humanity.

The most cruel and heinous aspect of this cultural war is that it targets children by putting them in colonial boarding schools –even children as young as 4 years old, too little and too vulnerable to be in a boarding school. Today these boarding schools house roughly one million children between ages 6 to 18. China kept another 100,000 children aged between four to six years old in boarding pre-schools. They have not only been subject to cultural assimilation but also ideological indoctrination as a strategy to manufacture a generation of model colonial subjects –rootless in their culture and toothless in their language.

This systematic policy of separating children from their families and subjecting them to cultural assimilation and ideological indoctrination is nothing but Cultural Genocide. Under this policy, Beijing is not only tearing families apart but also forcing vulnerable children to become strangers to their own culture by severing their spiritual, linguistic, and cultural ties to their home and community.

This has to be understood, not merely as an issue of taking away defenceless children from their families and brainwashing them, but in a more psychological and physiological sense of brutalizing children’s mind and body for political ends. And the traumatic experiences, they have to suffer, and the social and emotional tolls they will have on the people of Tibet in the future is not an uneasy thing to guess.

An absurdity, stretched beyond its limit, is Beijing’s justification for running the colonial boarding school system on the grounds that there are not enough schools in rural and remote Tibetan areas. However, the reality is that it is the same regime in Beijing that closed existing village-level as well as the few private schools in Tibet –leaving no alternatives for Tibetan students except the boarding schools.

Therefore, the real problem with Ragya School, in China’s eyes, is not that it does not have fancy buildings or expensive grounds. Instead, it stood in Beijing’s way of cultural and linguistic elimination in Tibet. This school has produced many modern educated students with strong roots in their culture and skilled in their mother tongue –making a positive impact in their respective field as educators, artists, intellectuals, writers, civil servants and entrepreneurs.

In the ultimate analysis, this forced closure of Tibetan medium schools is to terminate, not just an alternative school for the Tibetans but the very idea that it is not only possible, but also pedagogically more conducive for Tibetan students to excel academically if the medium of instruction is their own language.

Colonial system, whether yesterday or today, is intrinsically disempowering when it comes to the true interests and aspirations of the occupied people. In the case of Tibet, this has never been clearer than now. It is manifested in the form of political repression, economic marginalization and cultural suppression. The forced closure of Tibetan medium schools is another bomb China dropped on the soul of Tibetan people and civilization.

Tibetans, especially in Tibet, felt the crushing blow of this repression against their culture and language. The mournful scene from the last day of the school is, indeed a funeral rite –for an acclaimed school and the idea of such an alternative. Despite the enormous personal risks including the arrest and torture, many in Tibet expressed their sense of loss, sadness and helplessness after the school was shut down.

A line from the social media post of a Tibetan encapsulates the general mood in Tibet during that time ––“Even the agony of death may not be as excruciating as today’s event.”

(Views expressed are his own)

The author is an independent researcher and political analyst focusing on developments in Tibet, Chinese domestic politics, and foreign policy. He is based in North India.